- Home

- Practical Advice

- Garden habitats

- Water ecology

Introduction to water in the garden and pond ecology

By Steve Head and Adrian Thomas

Water is one of the key requirements for wildlife in gardens, just as everywhere else. All plants need water to grow, using it for transpiration to drive sap flow which is the equivalent of a blood system for moving nutrients around the body of the plant. Water is also a key ingredient, with carbon dioxide and light energy, for the creation of carbohydrates and from them, all the other constituents of the living plant. The plants in turn provide food for all animals, so it's obvious that water underpins all productivity in the garden.

Providing water in the garden

Watering The simplest way that almost all gardeners provide water is by artificially watering parts of the garden in dry weather. A very few of us are lucky enough to have a well, but otherwiase we have to rely on water butts or water from the tap. During drought periods, most butts are soon emptied, and if the drought is serious, hosepipe bans have to be imposed, because in dry spells watering the garden accounts for two thirds of household water use. With climate change uncertainties, and the growing cost of providing clean drinking water, it's important that gardeners become more aware of the sustainability issues of garden watering.

There are several leaflets available, often sponsored by water companies. This one by the RHS and Anglian Water is a useful guide to more efficient use of water in the garden. Look also at the RHS's own web pages starting at "Managing Water in the Garden".

Bird baths These are among the commonest wildlife featurs added to gardens, but in a study of 5 cities, Sheffield researchers found they were in only about 15% of gardens whose owners responded to a questionnaire1, compared with 29% for bird feeders or bird tables. They can be attractive sculptural; features im a garden as well as fulfilling a valuable role for many insects as well as birds.

Birds use their baths to drink as well as bathe, and like feeding stations they need to be properly designed, situated and kept clean. You will find useful advice on birdbaths from the RSPB here.

Garden Ponds Ponds are arguably the richest, most productive and engaging of all wildlife habitats in the garden, hosting a range of wildlife that would otherwise struggle to find a home there, and adding a whole new ecosystem. Even a small garden pond is likely to be colonised by some small invertebrates, and one that is medium-sized is likely to be busy in spring and summer with Common Frogs, newts and a selection of the commoner damselfly and dragonfly species.

Key pond species

Garden ponds host creatures that are entirely aquatic or almost so (such as pond snails, water beetles and backswimmers), others that spend a large part of their life cycle in water (such as frogs, toad, newts, dragonflies and damselflies), and ponds also provide drinking, feeding and bathing opportunities for a range of terrestrial creatures.

Pond flora inevitably includes many specialised species, including submerged or floating and emergent aquatic plants that are vital in creating the habitat structures which support the invertebrates. Read more about pond plants in our page Planting-up ponds.

A pretty - and rather typical garden pond.

It is larger than the 1m2 national average, and has a butyl liner. It has coping stones and rather steep sides which are not ideal for wildlife, but there are plenty of ways animals could find their way in or out through stones or vegetation

While we may have a good idea of what creatures can be found in garden ponds, there is still much detail we don't know and much assumption and, for some aspects, contradiction about what makes a good wildlife pond.

Creating a garden pond from scratch means quite a lot of work. Garden ponds have also had a major role in the spread of invasive aquatic plants, and ponds can pose safety issues for young children. For these reasons, while creating a garden pond is definitely something that should be considered by every gardener, it should be done with care and planning. See our page Creating ponds.

Pond Ecology

What's presented here is a very elementary account, but it is really useful to understand some aspects of pond ecology if you are going to manage your garden pond for wildlife. If you want to learn more we recommend The Pond Book2 by the Freshwater Habitats Trust and an old but still very useful article by the same team in British Wildlife3. A very academic and complete account is available from two Swedish scientists "The Biology of Lakes and Ponds"4.

Freshwater habitats generally

Freshwater habitats are often clased in two categories. "Lentic" is where the water is essentially still, including ponds, lakes and wetlands. The other category is "lotic" where the water is moving, as in streams and rivers. Some habitats such as ditches can be a bit of both at different times of water flow. We can also note the brackish water habitats of estuary rivers and wetlands, but these special sites aren't relevant to gardens.

Pond environment

Most garden ponds, and many countryside ponds too, are essentially closed ecosystems. They do recieve inputs of material from outside such as leaves and rainfall, and they do export adults of creatures which have larval stages in them, but generally what goes into a pond stays there, be it nutrients or debris, unless someone fishes it out. This makes them more sensitive to pollutants such as excess nutrients than do most other garden habitats.

Certain physical factors are important for ponds and the creature that live in them.

Water quality: Clean water is an essential component of a healthy wildlife pond. The best water to fill a pond is rainwater. Avoid diverting water from a ditch or stream, because at some times of year they may well be contaminated with pollutants, fertiliser or silt - and you would need a license to extract water. Tap water and run-off often contain nutrients in which make your pond more susceptible to algal blooms. Tap water also contains chlorine, although it naturally degrade over a few days. If at all possible, prevent the run-off of water into the pond that has passed through fertilised soil. This important topic is explained further in our leaflet by Ian Thornhill Clean water is key for wildlife ponds.

Oxygen and temperature These can be considered together, because the warmer water becomes, the less oxygen it can hold, and so the more stress animals can experience. At 5°C water holds 12.8 ml oxygen per litre, by 30°C it has fallen to 7.6ml/l 2.. In hot weather you can often see carp gasping an air and water mix at the pond surface, and if the water gets too hot, fish can be killed by oxygen lack. However, most invertebrate animals living in lentic (pond) conditions are adapted to low and fluctuating oxygen levels, so this isn't quite the problem some people assume.

Temperature of course depends on sunlight, so shaded ponds heat less than sunlit ponds, while shallow ponds heat up faster than deeper ones. An ideal wildlife pond could have shaded and sunlit areas, and a variety of (shallowish) depths, so creatures can move to the conditions that suit them.

Oxygen levels are also affected on a daily level by photosynthesis in the day driving up levels to saturation, and respiration by plants and animals at night bringing it back down. Windy days cause ripples which help to oxygenate the water, while decay of dead material at the bottom of a deeper pond can reduce local oxygen levels to zero. In the winter, ice and snow can build up on the top of the pond which acts as a duvet preventing further chilling - deep water stays at 4°C - but also prevents oxygen exchange at the surface, so deeper water over organic detritus can get rather anoxic, occasionally killing overwintering creature like frogs. However, as Jeremy Biggs recently discovered, in a clean shallow pond ice can actually raise oxygen levels, by limiting loss of oxygen without preventing photosynthesis!

In ponds with fish, we are often recomended to create "breathing holes" in ice, by floating a large ball, or putting a hot saucepan of water on the ice to melt through. In a hard winter these are at best very temporary solutions, and especially if you haven't got fish, there is probably little or no benefit.

Pond habitats

There are different parts of the pond with different creatures using them

Surface film habitat. Water has very high surface tension, making it possible for small creature like pond skaters to walk on the surface film where they feed on plants and debris. Conversely, the film is very difficult for small aquatic creatures to break through, so snails can hang upside down from surface film feeding on material accumulating just below he surface. Gnat and mosquito larvae use the film to support them while they breathe air through snorkels on their bottoms.

References

1. Gaston, K.J., Fuller, R.A., Loram, A., MacDonald, C., Power, S and Dempsey, N (2007). Urban domestic gardens (XI): variation in urban wildlife gardening in the UK. Biodiversity and Conservation 16, p 3227-3238

2. Williams, P., Biggs, J., Whitfield, M., Thorne,A., Bryant, S., Fox, G, and Nicolet, P. 1999. The Pond Book a guide to the management and creation of ponds. Ponds Conservation Trust Oxford

3. Biggs, J, Corfield, A., Walker, D., Whitfields M. and Williams, P. 1994. New apporaches to the management of ponds. British Wildlife 5:273-287

4. Brönmark, C. and Hansson L-A. 1998 The Biology of Lakes and Ponds. Oxford University Press.

5. Clean Water Team (CWT) 2004. Dissolved Oxygen Fact Sheet, FS-3.1.1.0(DO). in: The Clean Water Team Guidance Compendium for Watershed Monitoring and Assessment, Version 2.0. Division of Water Quality, California State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB), Sacramento, CA

Resources available from this page:

Open water habitat. This is most of the volume of the pond, between the surface layer, and the beginning of vegetation growth on the bottom and sides. Its most important inhabitants are the plankton, phytoplankton plants and zooplankton animals, including larval stages of animals which live elsewhere as adults. The open water is used by hunting fish, and in consequence is a dangerous place for small invertebrates, which largely avoid it in favour of the much safer and productive vegetation habitat.

Bottom habitat Pond bottoms range from un-covered liner with little except algal growth, through often rather inhospitable deep silt or peaty material, to sand and pebbles in which bottom living (submerged and emergent) plants can root. Many small detritivores (which eat debris) live within the bottom substrate, and where appropriate, larger animals such as swan mussels and crayfish, but neither do well in garden ponds, being more often found in lotic rather than lentic water bodies.

Vegetation habitat is the term we are using to describe the space among the roots, stems and leaves of plants living completely within the water, or rooted in there and growing out to flower. The tangle of living plant structure is immensely complex and part of the reason ponds can hold so many species. It is there where the bulk of interesting invertebrates can be found, so a pond without vegetation is a poor pond for animal life. Since most plants thrive in shallow water, it's the edge of the pond - indeed the top 5cm or so, that carries most of the life, but many creatures also use the habitat created by bottom-rooted plants.

Marginal habitat This is another very biologically rich area. It is where the pond meets the surrounding terrestrial habitat, and as pond levels go up and down, the area will be more or less flooded accordingly, and in that way is rather like the beach of a seashore. The marginal habitat grades downwards into well vegetated bottom and weed habitat with aquatic plants, and upwards into primarily land plants which like to get their feet wet. You can create large marginal pond zones by creating a bog garden.

For most garden ponds, concentrating on the vegetation and marginal habitats will give you the most wildlife.

Life above and below the surface film. Pond skater left - see the dimples it makes on the water film. Mosquito larvae right, hanging from the film with their snorkels.

Energy, material and food chains

Just as with the land habitats of gardens, ponds cycle energy, nutrients and biomass within their enclosed ecosystem, see our page on food webs for background. Unlike the rest of the garden, the exchange of material and nutrients in and out is crucial in understanding many pond problems. As semi-closed systems, materials that go into a garden pond tend to stay there and accumulate.

Energy sources - Light from the sky is overwhelmingly the most important source of energy for pond ecosystems, but they also receive natural inputs from leaves and debris falling in, and un-natural inputs of any fish or duck food you might throw in. These inputs can significantly unbalance a pond's ecology

Key nutrients As with terrestrial plants, pond plants need C02 and soluble ions of nitrogen, potassium and phosphorous to grow, plus the usual variety of minor and trace elements. In ponds, carbon dioxide is never limiting as it is very soluble in water. The key limiting nutrient in freshwater systems is generally phosphorous as phosphates, and its level is used to determine if a water body is of low productivity (oligotrophic) with levels of phosphate around 5-10μg/l, mesotrophic with levels at 10-30μg/l or very productive with phosphate levels of 30-100μg/l. Ponds and lakes polluted by nutrient run-off can go up to much higher levels.

When ponds become enriched and highly eutrophic, vegetation growth can go mad, especially in the form of phytoplankton causing pea-soup water conditions, blanketweed covering the surface of the pond (and submerged structures) or duckweed floating at the top. While natural, this is unsightly and gardeners will want to remove it, but this is only really possible by attacking the basic problem of excessive nutrients.

Primary producers Unlike land habitats, ponds have two sets of primary producers, the large plants like those on land, and the phytoplankton, minute single celled or multicellular algae which swim or are suspended in the water. They are very important ecosystem drivers, since they are the base of the food chain for filter-feeding herbivores such as tiny crustaceans which in turn are the food for many carnivorous animals.and higher plants. The two sorts of primary producers create two classes of food chain in ponds as shown below.

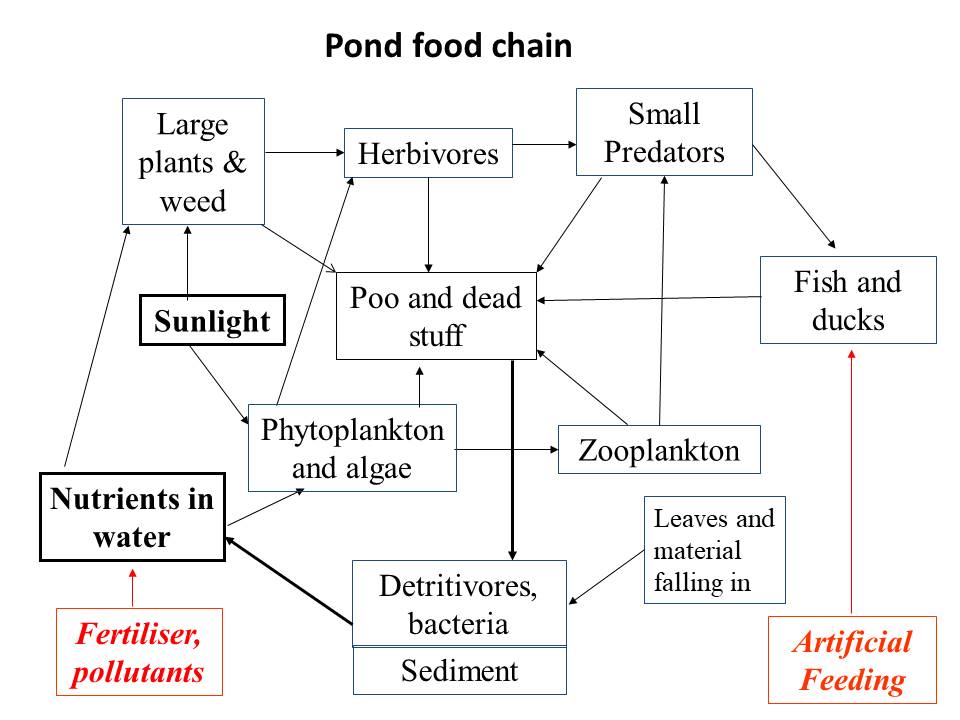

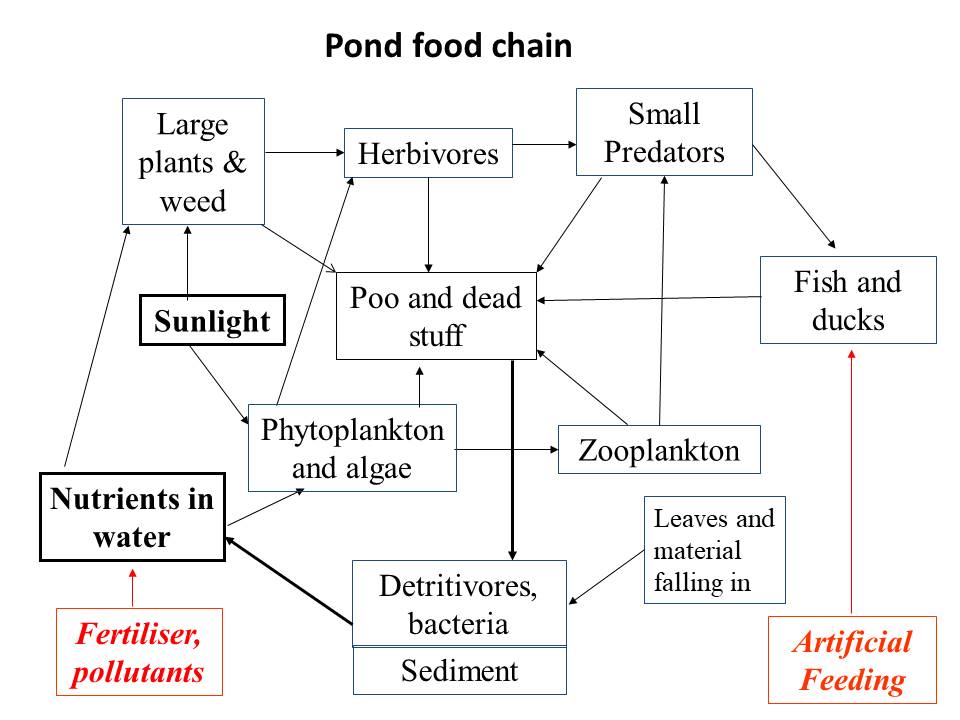

This diagram shows the planktonic food chain as well as the large plant chain. It also shows the hugely important role of detritivores and bacteria, in breaking down the large amounts of decaying matter and excreta produced by everything else in the pond. Some of this waste is incorporated in sediment, but crucially the rest is broken back down to the nutrients that drive the system, together with sunlight.

When ponds go bad... is usually because the system has got out of balance by excessive inputs of nutrients. This is a problem in many garden ponds, which tend to be eutrophic, with low biological diversity, and prone to out-of-control blanketweed and other problems. Since garden ponds are very small, nutrient imbalances occur easily, especially since most of them contain fish which are fed regularly, providing a major source of nutrients into the water. The same issues arise from surface run-off entering the pond from fertilised veggie patches, lawns and flowerbeds. When this happens, other undesirable pollutants can also get in, and many pond inhabitants are very sensitive to pesticides and herbicides

A classic sick and rather revolting pond. The wrecked cars, tyres and no doubt other horrors may be adding pollution, but the main problem is a very high nutrient content that results in the pond being smothered with blanket weed.

It is likely that little oxygen reaches the lower water depths, and that the botton water is sulphurous and toxic.

Ponds and Succession

Succession is the process where habitats and wildlife areas change naturally through time, as one set of species becomes sequentially replaced by others. This can result from major environmental change such as happened in the UK after the last ice age left essentially bare ground for colonists about 11,500 years ago. Fast colonists like birch gave way to pine, and then to broadleafed forests of oak and ash. At a smaller level, succession works on all disturbed habitats, generally bringing them back to what is often called a "climax state" dominated by the species best equipped to survive in the long term. In Britain this is generally thought to be oak woodland, unless soil, water and human interference factors hold it back. A neglected garden swiftly becomes dominated by nettles and brambles, followed by ivy, holly and sycamore trees.

Ponds tend to show successional processes, because they accumulate material in their deeper waters, while reeds grow in from the edge. Quite quickly most ponds can become shallower, while the outer margins become marshy and begin to support trees like aspen and willow. This isn't always the case, because ponds that regularly dry out in summer tend to "burn off" accumulated peaty material, and can keep going for ages. Very oligotrophic ponds with minimal silt input can last a long time long too.

Garden ponds are small, generally very productive, and show strong successional tendencies, depending on what plants you put in. If you have added reeds or reedmace, even a larger garden pond can become permanently covered with vegetation in only a few years, and on a seasonal basis the same can happen with larger water lilies and even bogbean. Ecologically, there is nothing wrong with this happening, succession is a natural process, and indeed ponds support different and important species as all stages from a bare hole in the ground through to semi-terrestrial wetland. In an ideal world, gardeners would allow their ponds to continue natural sucession, and instead dig new ponds to maintain early successional open water.

In practice, gardeners want a pond to be pretty as well as biodiverse, so they need to manage their pond to hold back succession. This usually means cutting out large quantities of plant material once or even twice a year, and periodically remove excessive dead leaves and muck from the bottom of the pond. Obviously this is best done when pond life is at its least active, generally in the late autumn/early winter before it gets so cold you can't be bothered. For more about pond management see our page on Managing Garden Ponds.

Introduction to water in the garden and pond ecology

By Steve Head and Adrian Thomas

Water is one of the key requirements for wildlife in gardens, just as everywhere else. All plants need water to grow, using it for transpiration to drive sap flow which is the equivalent of a blood system for moving nutrients around the body of the plant. Water is also a key ingredient, with carbon dioxide and light energy, for the creation of carbohydrates and from them, all the other constituents of the living plant. The plants in turn provide food for all animals, so it's obvious that water underpins all productivity in the garden.

Providing water in the garden

Watering The simplest way that almost all gardeners provide water is by artificially watering parts of the garden in dry weather. A very few of us are lucky enough to have a well, but otherwise we have to rely on water butts or water from the tap. During drought periods, most butts are soon emptied, and if the drought is serious, hosepipe bans have to be imposed, because in dry spells watering the garden accounts for two thirds of household water use. With climate change uncertainties, and the growing cost of providing clean drinking water, it's important that gardeners become more aware of the sustainability issues of garden watering.

There are several leaflets available, often sponsored by water companies. This one by the RHS and Anglian Water is a useful guide to more efficient use of water in the garden. Look also at the RHS's own web pages starting at "Managing Water in the Garden".

Bird baths These are among the commonest wildlife featurs added to gardens, but in a study of 5 cities, Sheffield researchers found they were in only about 15% of gardens whose owners responded to a questionnaire1, compared with 29% for bird feeders or bird tables. They can be attractive sculptural; features in a garden as well as fulfilling a valuable role for many insects as well as birds.

Birds use their baths to drink as well as bathe, and like feeding stations, they need to be properly designed, situated and kept clean. You will find useful advice on birdbaths from the RSPB here and in our How-to guide.

Garden Ponds Ponds are arguably the richest, most productive and engaging of all habitats in the garden, hosting a range of wildlife that would otherwise struggle to find a home there, effectively adding a whole new ecosystem. Even a small garden pond is likely to be colonised by some small invertebrates, and one that is medium-sized is likely to be busy in spring and summer with common frogs, newts and a selection of the commoner damselfly and dragonfly species.

Introduction to water in the garden and pond ecology

By Steve Head and Adrian Thomas

Water is one of the key requirements for wildlife in gardens, just as everywhere else. All plants need water to grow, using it for transpiration to drive sap flow which is the equivalent of a blood system for moving nutrients around the body of the plant. Water is also a key ingredient, with carbon dioxide and light energy, for the creation of carbohydrates and from them, all the other constituents of the living plant. The plants in turn provide food for all animals, so it's obvious that water underpins all productivity in the garden.

Providing water in the garden

Watering The simplest way that almost all gardeners provide water is by artificially watering parts of the garden in dry weather. A very few of us are lucky enough to have a well, but otherwise we have to rely on water butts or water from the tap. During drought periods, most butts are soon emptied, and if the drought is serious, hosepipe bans have to be imposed, because in dry spells watering the garden accounts for two thirds of household water use. With climate change uncertainties, and the growing cost of providing clean drinking water, it's important that gardeners become more aware of the sustainability issues of garden watering.

There are several leaflets available, often sponsored by water companies. This one by the RHS and Anglian Water is a useful guide to more efficient use of water in the garden. Look also at the RHS's own web pages starting at "Managing Water in the Garden".

Bird baths These are among the commonest wildlife featurs added to gardens, but in a study of 5 cities, Sheffield researchers found they were in only about 15% of gardens whose owners responded to a questionnaire1, compared with 29% for bird feeders or bird tables. They can be attractive sculptural; features in a garden as well as fulfilling a valuable role for many insects as well as birds.

Birds use their baths to drink as well as bathe, and like feeding stations, they need to be properly designed, situated and kept clean. You will find useful advice on birdbaths from the RSPB here and in our How-to guide.

Garden Ponds Ponds are arguably the richest, most productive and engaging of all habitats in the garden, hosting a range of wildlife that would otherwise struggle to find a home there, effectively adding a whole new ecosystem. Even a small garden pond is likely to be colonised by some small invertebrates, and one that is medium-sized is likely to be busy in spring and summer with common Frogs, newts and a selection of the commoner damselfly and dragonfly species.

Above: A pretty - and rather typical garden pond.

It is larger than the 1m2 national average, and has a butyl liner. It has coping stones and rather steep sides which are not ideal for wildlife, but there are plenty of ways animals could find their way in or out through stones or vegetation

While we may have a good idea of what creatures can be found in garden ponds, there is still much detail we don't know and much assumption and, for some aspects, contradiction about what makes a good wildlife pond.

Creating a garden pond from scratch means quite a lot of work. Garden ponds have also had a major role in the spread of invasive aquatic plants, and ponds can pose safety issues for young children. For these reasons, while creating a garden pond is definitely something that should be considered by every gardener, it should be done with care and planning. See our page Creating ponds.

Key pond species

Garden ponds host creatures that are entirely aquatic or almost so (such as pond snails, water beetles and backswimmers), others that spend a large part of their life cycle in water (such as frogs, toad, newts, dragonflies and damselflies), and ponds also provide drinking, feeding and bathing opportunities for a range of terrestrial creatures.

Pond flora inevitably includes many specialised species, including submerged or floating and emergent aquatic plants that are vital in creating the habitat structures which support the invertebrates. Read more about pond plants in our page Planting-up ponds.

Pond Ecology

What's presented here is a very elementary account, but it is really useful to understand some aspects of pond ecology if you are going to manage your garden pond for wildlife. If you want to learn more we recommend The Pond Book2 by the Freshwater Habitats Trust and an old but still very useful article by the same team in British Wildlife3. A very academic and complete account is available from two Swedish scientists "The Biology of Lakes and Ponds"4.

Freshwater habitats generally

Freshwater habitats are often clased in two categories. "Lentic" is where the water is essentially still, including ponds, lakes and wetlands. The other category is "lotic" where the water is moving, as in streams and rivers. Some habitats such as ditches can be a bit of both at different times of water flow. We can also note the brackish water habitats of estuary rivers and wetlands, but these special sites aren't relevant to gardens.

Pond environment

Most garden ponds, and many countryside ponds too, are essentially closed ecosystems. They do recieve inputs of material from outside such as leaves and rainfall, and they do export adults of creatures which have larval stages in them, but generally what goes into a pond stays there, be it nutrients or debris, unless someone fishes it out. This makes them more sensitive to pollutants such as excess nutrients than do most other garden habitats.

Certain physical factors are important for ponds and the creature that live in them.

Water quality: Clean water is an essential component of a healthy wildlife pond. The best water to fill a pond is rainwater. Avoid diverting water from a ditch or stream, because at some times of year they may well be contaminated with pollutants, fertiliser or silt - and you would need a license to extract water. Tap water and run-off often contain nutrients in which make your pond more susceptible to algal blooms. Tap water also contains chlorine, although it naturally degrade over a few days. If at all possible, prevent the run-off of water into the pond that has passed through fertilised soil. This important topic is explained further in our leaflet by Ian Thornhill Clean water is key for wildlife ponds.

Oxygen and temperature These can be considered together, because the warmer water becomes, the less oxygen it can hold, and so the more stress animals can experience. At 5°C water holds 12.8 ml oxygen per litre, by 30°C it has fallen to 7.6ml/l 2.. In hot weather you can often see carp gasping an air and water mix at the pond surface, and if the water gets too hot, fish can be killed by oxygen lack. However, most invertebrate animals living in lentic (pond) conditions are adapted to low and fluctuating oxygen levels, so this isn't quite the problem some people assume.

Temperature of course depends on sunlight, so shaded ponds heat less than sunlit ponds, while shallow ponds heat up faster than deeper ones. An ideal wildlife pond could have shaded and sunlit areas, and a variety of (shallowish) depths, and creatures can move to the conditions that suit them.

Oxygen levels are also affected on a daily level by photosynthesis in the day driving up levels to saturation, and respiration by plants and animals at night bringing it back down. Windy days cause ripples which help to oxygenate the water, while decay of dead material at the bottom of a deeper pond can reduce local oxygen levels to zero. In the winter, ice and snow can build up on the top of the pond which acts as a duvet preventing further chilling - deep water stays at 4°C - but also prevents oxygen exchange at the surface, so deeper water over organic detritus can get rather anoxic, occasionally killing overwintering creature like frogs. However, as Jeremy Biggs recently discovered, in a clean shallow pond ice can actually raise oxygen levels, by limiting loss of oxygen without preventing photosynthesis!

In ponds with fish, we are often recomended to create "breathing holes" in ice, by floating a large ball, or putting a hot saucepan of water on the ice to melt through. In a hard winter these are at best very temporary solutions, and especially if you haven't got fish, there is probably little or no benefit.

Pond habitats

There are different parts of the pond with different creatures using them

Surface film habitat. Water has very high surface tension, making it possible for small creature like pond skaters to walk on the surface film where they feed on plants and debris. Conversely, the film is very difficult for small aquatic creatures to break through, so snails can hang upside down from surface film feeding on material accumulating just below he surface. Gnat and mosquito larvae use the film to support them while they breathe air through snorkels on their bottoms.

Life above and below the surface film. Pond skater left - see the dimples it makes on the water film. Mosquito larvae right, hanging from the film with their snorkels.

Energy, material and food chains

Just as with the land habitats of gardens, ponds cycle energy, nutrients and biomass within their enclosed ecosystem, see our page on food webs for background. Unlike the rest of the garden, the exchange of material and nutrients in and out is crucial in understanding many pond problems. As semi-closed systems, materials that go into a garden pond tend to stay there and accumulate.

Energy sources - Light from the sky is overwhelmingly the most important source of energy for pond ecosystems, but they also receive natural inputs from leaves and debris falling in, and un-natural inputs of any fish or duck food you might throw in. These inputs can significantly unbalance a pond's ecology

Key nutrients As with terrestrial plants, pond plants need C02 and soluble ions of nitrogen, potassium and phosphorous to grow, plus the usual variety of minor and trace elements. In ponds, carbon dioxide is never limiting as it is very soluble in water. The key limiting nutrient in freshwater systems is generally phosphorous as phosphates, and its level is used to determine if a water body is of low productivity (oligotrophic) with levels of phosphate around 5-10μg/l, mesotrophic with levels at 10-30μg/l or very productive with phosphate levels of 30-100μg/l. Ponds and lakes polluted by nutrient run-off can go up to much higher levels.

When ponds become enriched and highly eutrophic, vegetation growth can go mad, especially in the form of phytoplankton causing pea-soup water conditions, blanketweed covering the surface of the pond (and submerged structures) or duckweed floating at the top. While natural, this is unsightly and gardeners will want to remove it, but this is only really possible by attacking the basic problem of excessive nutrients.

Primary producers Unlike land habitats, ponds have two sets of primary producers, the large plants like those on land, and the phytoplankton, minute single celled or multicellular algae which swim or are suspended in the water. They are very important ecosystem drivers, since they are the base of the food chain for filter-feeding herbivores such as tiny crustaceans which in turn are the food for many carnivorous animals.and higher plants. The two sorts of primary producers create two classes of food chain in ponds as shown below.

Open water habitat. This is most of the volume of the pond, between the surface layer, and the beginning of vegetation growth on the bottom and sides. Its most important inhabitants are the plankton, phytoplankton plants and zooplankton animals, including larval stages of animals which live elsewhere as adults. The open water is used by hunting fish, and in consequence is a dangerous place for small invertebrates, which largely avoid it in favour of the much safer and productive vegetation habitat.

Bottom habitat Pond bottoms range from un-covered liner with little except algal growth, through often rather inhospitable deep silt or peaty material, to sand and pebbles in which bottom living (submerged and emergent) plants can root. Many small detritivores (which eat debris) live within the bottom substrate, and where appropriate, larger animals such as swan mussels and crayfish, but neither do well in garden ponds, being more often found in lotic rather than lentic water bodies.

Vegetation habitat is the term we are using to describe the space among the roots, stems and leaves of plants living completely within the water, or rooted in there and growing out to flower. The tangle of living plant structure is immensely complex and part of the reason ponds can hold so many species. It is there where the bulk of interesting invertebrates can be found, so a pond without vegetation is a poor pond for animal life. Since most plants thrive in shallow water, it's the edge of the pond - indeed the top 5cm or so, that carries most of the life, but many creatures also use the habitat created by bottom-rooted plants.

Marginal habitat This is another very biologically rich area. It is where the pond meets the surrounding terrestrial habitat, and as pond levels go up and down, the area will be more or less flooded accordingly, and in that way is rather like the beach of a seashore. The marginal habitat grades downwards into well vegetated bottom and weed habitat with aquatic plants, and upwards into primarily land plants which like to get their feet wet. You can create large marginal pond zones by creating a bog garden.

For most garden ponds, concentrating on the vegetation and marginal habitats will give you the most wildlife.

A classic sick and rather revolting pond. The wrecked cars, tyres and no doubt other horrors may be adding pollution, but the main problem is a very high nutrient content that results in the pond being smothered with blanket weed.

It is likely that little oxygen reaches the lower water depths, and that the botton water is sulphurous and toxic.

This diagram shows the planktonic food chain as well as the as the large plant chain. It also shows the hugely important role of detritivores and bacteria, in breaking down the large amounts of decaying matter and excreta produced by everything else in the pond. Some of this waste is incorporated in sediment, but crucially the rest is broken back down to the nutrients that drive the system, together with sunlight.

When ponds go bad... is usually because the system has got out of balance by excessive inputs of nutrients. This is a problem in many garden ponds, which tend to be eutrophic, with low biological diversity, and prone to out-of-control blanketweed and other problems. Since garden ponds are very small, nutrient imbalances occur easily, especially since most of them contain fish which are fed regularly, providing a major source of nutrients into the water. The same issues arise from surface run-off entering the pond from fertilised veggie patches, lawns and flowerbeds. When this happens, other undesirable pollutants can also get in, and many pond inhabitants are very sensitive to pesticides and herbicides

Ponds and Succession

Succession is the process where habitats and wildlife areas change naturally through time, as one set of species becomes sequentially replaced by others. This can result from major environmental change such as happened in the UK after the last ice age left essentially bare ground for colonists about 11,500 years ago. Fast colonists like birch gave way to pine, and then to broadleafed forests of oak and ash. At a smaller level, succession works on all disturbed habitats, generally bringing them back to what is often called a "climax state" dominated by the species best equipped to survive in the long term. In Britain this is generally thought to be oak woodland, unless soil, water and human interference factors hold it back. A neglected garden swiftly becomes dominated by nettles and brambles, followed by ivy, holly and sycamore trees.

Ponds tend to show successional processes, because they accumulate material in their deeper waters, while reeds grow in from the edge. Quite quickly most ponds can become shallower, while the outer margins become marshy and begin to support trees like aspen and willow. This isn't always the case, because ponds that regularly dry out in summer tend to "burn off" accumulated peaty material, and can keep going for ages. Very oligotrophic ponds with minimal silt input can last a long time long too.

Garden ponds are small, generally very productive, and show strong successional tendencies, depending on what plants you put in. If you have added reeds or reedmace, even a larger garden pond can become permanently covered with vegetation in only a few years, and on a seasonal basis the same can happen with larger water lilies and even bogbean. Ecologically, there is nothing wrong with this happening, succession is a natural process, and indeed ponds support different and important species as all stages from a bare hole in the ground through to semi-terrestrial wetland. In an ideal world, gardeners would allow their ponds to continue natural sucession, and instead dig new ponds to maintain early successional open water.

In practice, gardeners want a pond to be pretty as well as biodiverse, so they need to manage their pond to hold back succession. This usually means cutting out large quantities of plant material once or even twice a year, and periodically remove excessive dead leaves and muck from the bottom of the pond. Obviously this is best done when pond life is at its least active, generally in the late autumn/early winter before it gets so cold you can't be bothered. For more about pond management see our page on Managing Garden Ponds.

References

1. Gaston, K.J., Fuller, R.A., Loram, A., MacDonald, C., Power, S and Dempsey, N (2007). Urban domestic gardens (XI): variation in urban wildlife gardening in the UK. Biodiversity and Conservation 16, p 3227-3238

2. Williams, P., Biggs, J., Whitfield, M., Thorne,A., Bryant, S., Fox, G, and Nicolet, P. 1999. The Pond Book a guide to the management and creation of ponds. Ponds Conservation Trust Oxford

3. Biggs, J, Corfield, A., Walker, D., Whitfields M. and Williams, P. 1994. New apporaches to the management of ponds. British Wildlife 5:273-287

4. Brönmark, C. and Hansson L-A. 1998 The Biology of Lakes and Ponds. Oxford University Press.

5. Clean Water Team (CWT) 2004. Dissolved Oxygen Fact Sheet, FS-3.1.1.0(DO). in: The Clean Water Team Guidance Compendium for Watershed Monitoring and Assessment, Version 2.0. Division of Water Quality, California State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB), Sacramento, CA

Resources available from this page: