- Home

- Practical Advice

- Garden management

- Compost and fertility

Compost and Fertility

For fast-growing plants like most vegetables to grow well, they need good fertile soil. So do some ornamental plants, but many of the world’s plants evolved to grow on poor soils, and such plants generally grow slowly, however fertile the soil. It also pays to remember that if you’re trying to create a ‘wildflower meadow’, a fertile soil will tend to encourage the growth of the ‘wrong’ kind of plants, especially coarse grasses. Most weeds also love a fertile soil. The bottom line is that for the wildlife gardener, high fertility isn’t always beneficial. Nevertheless most gardeners strive to maintain a ‘good fertile soil’, defined as one with adequate amounts of plant nutrients, plenty of organic matter to help structure, drainage and moisture, a close to neutral pH (acidity), and huge quantities of beneficial bacteria and other microorganisms. As a gardener, your job is to monitor the condition of your soil, and adjust it when necessary to maintain the fertility level you need.

Getting good crops of vegetables needs healthy fertile soil

Plant nutrients

The most important elements needed by plants are nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P) and potassium (K), and “NPK” is the chemical basis of all general garden fertilisers. Fertilisers can be applied as mulch, slow release granules, or as rapid action liquid feeds or foliage sprays.

Organic gardeners, who don’t use synthetic chemicals, build fertility through crop rotation (involving nitrogen fixing crops like legumes), using lots of farmyard manure, or products such as bone meal, seaweed extracts, hoof & horn, “fish blood and bone” and fish meal. Organic fertiliser can also be made for garden use from very smelly infusions of rotted plants, especially comfrey and nettles.

Conventional gardeners can build fertility with the same techniques as organic gardeners, but most people use more concentrated mined phosphates, synthetic chemicals like ammonium nitrate and sulphate, potassium chloride and sulphate, superphosphate and mixes of these chemicals in NPK fertilisers such as “Growmore”.

Phosphorous and potassium tend to be abundant and retained in soil, although both are usually locked away in insoluble phosphate compounds, or bound with clay, which is why they are included in fertilisers in a readily available form.

Natural mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic connections with most plant roots, and help unlock the bound phosphate (as well as improving water uptake and helping to control pathogens), so encouraging these fungi helps plants to succeed. Mycorrhizal fungi are damaged by fungicide application, by cultivation, and by too much fertiliser application. You can buy cultured mycorrhizal fungi to put around the roots when planting shrubs or perennials, but since the fungi are normally present in soil anyway it's doubtful if this is useful.

A culture of mycorrhizal fungus growing on a laboratory petri dish

Trace elements

As well as the big three NPK elements, plants need trace quantities of many more elements, including sulphur, magnesium, iron, cobalt and many more. Occasionally these can be limiting (especially on chalky soils), and application of liquid kelp feeds is a good way to keep up the levels.

Iron is often bound up by chalky soils, and iron-chelating compounds (eg sequestrene) can allow lime-hating plants like magnolias, and azaleas to grow better on somewhat alkaline soils. A deficiency – or occasionally an excess – of trace elements is often an indication of an extreme pH (either too acid or too alkaline), rather than an absolute shortage.

Bird’s foot trefoil, a nitrogen fixing plant, and a good wildflower to plant for butterfly caterpillars

Nitrogen: the most important fertiliser

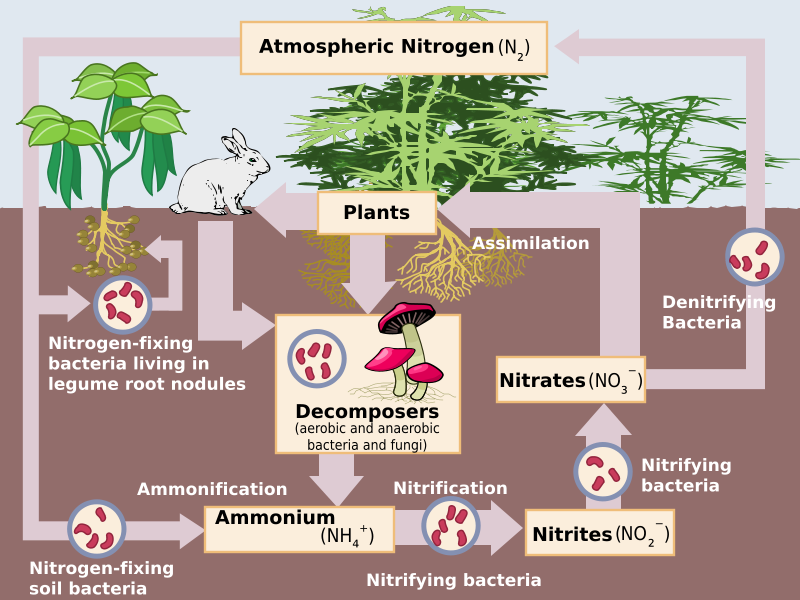

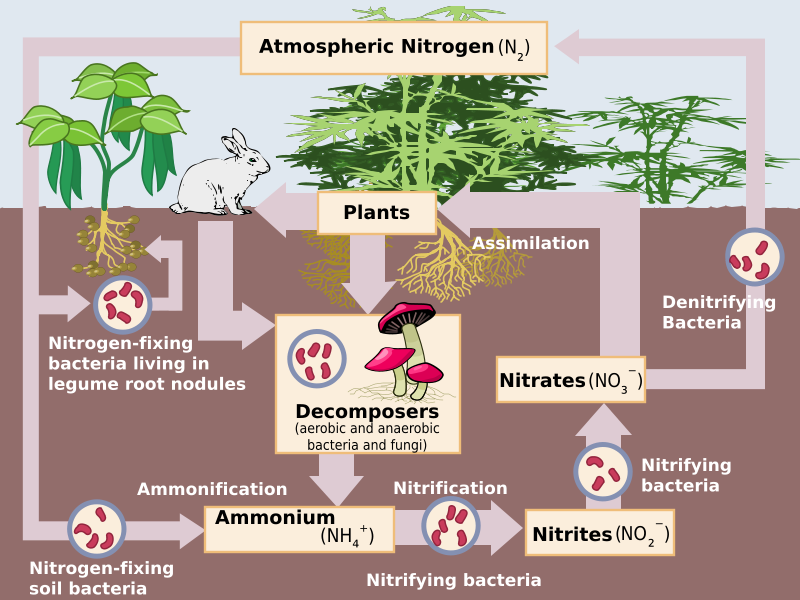

Nitrogen is the most limiting nutrient in most gardens and allotments. It is used by plants in the form of nitrates, and is built up naturally in the soil by nitrogen-fixing bacteria (and cyanobacteria or blue-green algae).

These are also found living symbiotically in plant root nodules, mainly in leguminous plants like beans and vetches, but in some others as well (e.g. alder, water fern, Elaeagnus and Gunnera). Prior to artificial fertilisers, farmers relied on clover leys in a rotation to build fertility through nitrogen fixation, and this remains a major technique in organic farming.

Nitrogen in soil is taken up by plants, broken down and lost by the action of other bacteria, and is maintained through the nitrogen cycle shown below.

How much fertiliser?

Manufacturers and retailers naturally encourage us to use lots of fertiliser, but overuse is expensive and wasteful.

Fertiliser from fields or gardens can cause big problems when excess runs off into ponds or streams, where it causes eutrophication, overgrowth of algae and competitive plants, and reduces the number of animal species that can flourish. High nutrient content in established garden soils is the main reason why it is so difficult to create functional wildflower meadows in most gardens, because fast-growing grasses, which love nitrogen, out-grow and smother the flowers. Artificial fertilisers are also very expensive in energy, so to garden sustainably we should be careful in their use.

There is plenty of advice on garden fertilisers in good gardening books or websites such as the Royal Horticultural Society's. Our advice would generally be to be mean with fertiliser, which will be good for the environment and your pocket.

Compost

Soil condition is probably more significant than high nutrient status for most gardens, and this is where compost comes into its own. Compost, or humus, is what remains after the earlier stages of the decay of plant (and animal) material. Good garden compost is a rich brown moist crumbly material which you make from weeds, prunings, lawn clippings and vegetable kitchen waste. Compost is a superb soil mulch and conditioner, and it is the best way to dispose of your organic garden and kitchen waste, saving it from the dustbin and landfill site.

It is easy to make your own compost, even in a very small garden. The RHS has some excellent advice on composting or we can recommend Ken Thompson's own book "Compost: The natural way to make food for your garden"

See also: Food webs and feeding roles

Download our "How to" guides:

How to: Make your own compost

Page writen by Ken Thompson Reviewed by Steve Head

Compost and Fertility

For fast-growing plants like most vegetables to grow well, they need good fertile soil. So do some ornamental plants, but many of the world’s plants evolved to grow on poor soils, and such plants generally grow slowly, however fertile the soil. It also pays to remember that if you’re trying to create a ‘wildflower meadow’, a fertile soil will tend to encourage the growth of the ‘wrong’ kind of plants, especially coarse grasses. Most weeds also love a fertile soil. The bottom line is that for the wildlife gardener, high fertility isn’t always beneficial.

Nevertheless most gardeners strive to maintain a ‘good fertile soil’, defined as one with adequate amounts of plant nutrients, plenty of organic matter to help structure, drainage and moisture, a close to neutral pH (acidity), and huge quantities of beneficial bacteria and other microorganisms. As a gardener, your job is to monitor the condition of your soil, and adjust it when necessary to maintain the fertility level you need.

Getting good crops of vegetables needs healthy fertile soil

Plant nutrients

The most important elements needed by plants are nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P) and potassium (K), and “NPK” is the chemical basis of all general garden fertilisers. Fertilisers can be applied as mulch, slow release granules, or as rapid action liquid feeds or foliage sprays.

Organic gardeners, who don’t use synthetic chemicals, build fertility through crop rotation (involving nitrogen fixing crops like legumes), using lots of farmyard manure, or products such as bone meal, seaweed extracts, hoof & horn, “fish blood and bone” and fish meal. Organic fertiliser can also be made for garden use from very smelly infusions of rotted plants, especially comfrey and nettles.

Conventional gardeners can build fertility with the same techniques as organic gardeners, but most people use more concentrated mined phosphates, synthetic chemicals like ammonium nitrate and sulphate, potassium chloride and sulphate, superphosphate and mixes of these chemicals in NPK fertilisers such as “Growmore”.

Phosphorous and potassium tend to be abundant and retained in soil, although both are usually locked away in insoluble phosphate compounds, or bound with clay, which is why they are included in fertilisers in a readily available form.

Natural mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic connections with most plant roots, and help unlock the bound phosphate (as well as improving water uptake and helping to control pathogens), so encouraging these fungi helps plants to succeed. Mycorrhizal fungi are damaged by fungicide application, by cultivation, and by too much fertiliser application. You can buy cultured mycorrhizal fungi to put around the roots when planting shrubs or perennials, but since the fungi are normally present in soil anyway it's doubtful if this is useful.

A culture of mycorrhizal fungus growing on a laboratory petri dish

Trace elements

As well as the big three NPK elements, plants need trace quantities of many more elements, including sulphur, magnesium, iron, cobalt and many more. Occasionally these can be limiting (especially on chalky soils), and application of liquid kelp feeds is a good way to keep up the levels.

Iron is often bound up by chalky soils, and iron-chelating compounds (eg sequestrene) can allow lime-hating plants like magnolias, and azaleas to grow better on somewhat alkaline soils. A deficiency – or occasionally an excess – of trace elements is often an indication of an extreme pH (either too acid or too alkaline), rather than an absolute shortage.

Bird’s foot trefoil, a nitrogen fixing plant, and an excellent wildflower to plant for butterfly caterpillars

Nitrogen: the most important fertiliser

Nitrogen is the most limiting nutrient in most gardens and allotments. It is used by plants in the form of nitrates, and is built up naturally in the soil by nitrogen-fixing bacteria (and cyanobacteria or blue-green algae).

These are also found living symbiotically in plant root nodules, mainly in leguminous plants like beans and vetches, but in some others as well (e.g. alder, water fern, Elaeagnus and Gunnera). Prior to artificial fertilisers, farmers relied on clover leys in a rotation to build fertility through nitrogen fixation, and this remains a major technique in organic farming.

Nitrogen in soil is taken up by plants, broken down and lost by the action of other bacteria, and is maintained through the nitrogen cycle shown below.

How much fertiliser?

Manufacturers and retailers naturally encourage us to use lots of fertiliser, but overuse is expensive and wasteful.

Fertiliser from fields or gardens can cause big problems when excess runs off into ponds or streams, where it causes eutrophication, overgrowth of algae and competitive plants, and reduces the number of animal species that can flourish. High nutrient content in established garden soils is the main reason why it is so difficult to create functional wildflower meadows in most gardens, because fast-growing grasses, which love nitrogen, out-grow and smother the flowers. Artificial fertilisers are also very expensive in energy, so to garden sustainably we should be careful in their use.

There is plenty of advice on garden fertilisers in good gardening books or websites such as the Royal Horticultural Society's. Our advice would generally be to be mean with fertiliser, which will be good for the environment and your pocket.

Compost

Soil condition is probably more significant than high nutrient status for most gardens, and this is where compost comes into its own. Compost, or humus, is what remains after the earlier stages of the decay of plant (and animal) material. Good garden compost is a rich brown moist crumbly material which you make from weeds, prunings, lawn clippings and vegetable kitchen waste. Compost is a superb soil mulch and conditioner, and it is the best way to dispose of your organic garden and kitchen waste, saving it from the dustbin and landfill site.

It is easy to make your own compost, even in a very small garden. The RHS has some excellent advice on composting or we can recommend Ken Thompson's own book "Compost: The natural way to make food for your garden"

See also: Food webs and feeding roles

Download our "How to" guides:

How to: Make your own compost

Page writen by Ken Thompson Reviewed by Steve Head